My December trip to Massachusetts not only included a look at King Philip Rock in Berlin (see Rock of King). A few days later, after Christmas and an ice storm swept through, I headed up to Princeton, Massachusetts to take a look at another prominent stone from that era: Redemption Rock.

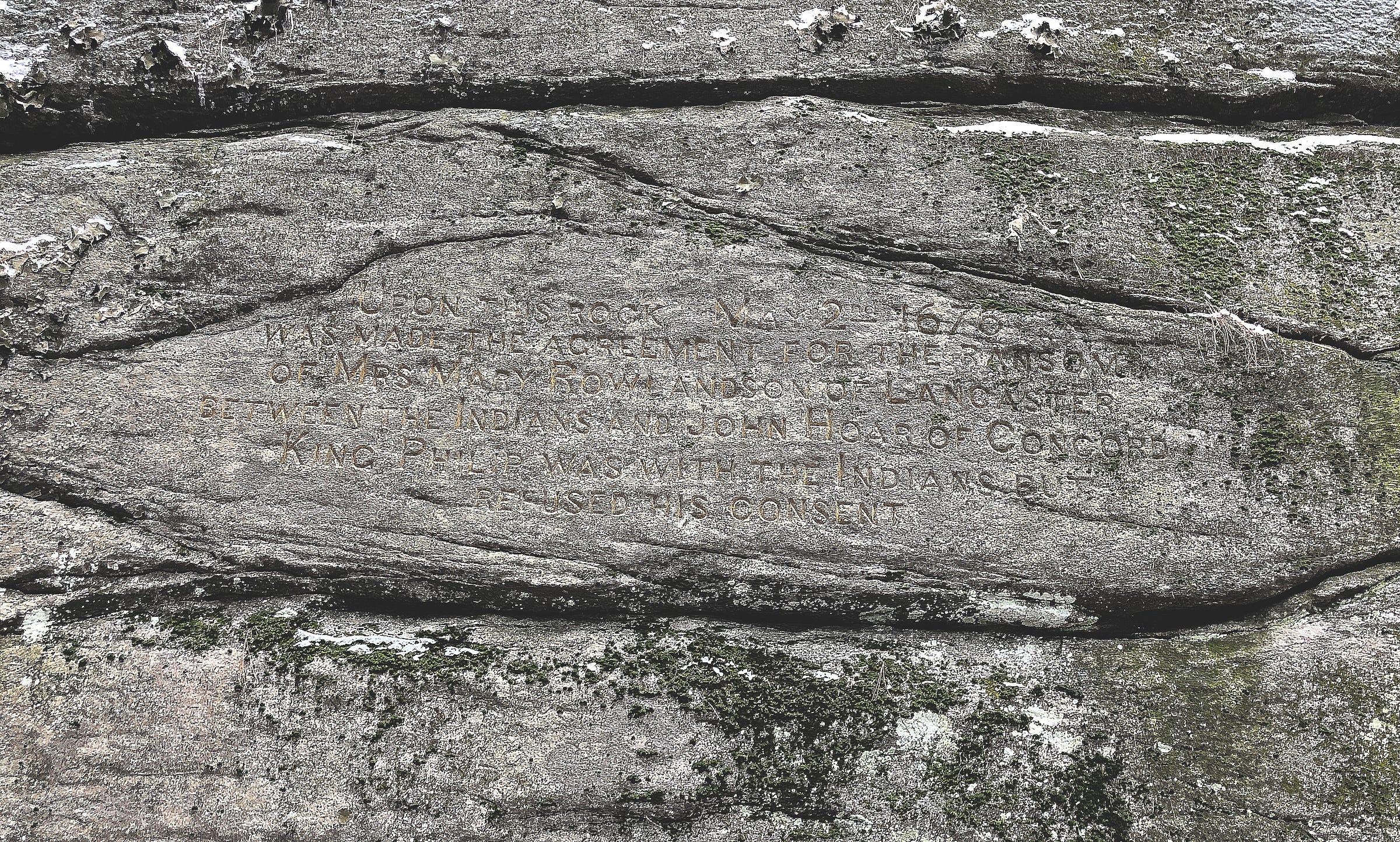

Unlike King Philip Rock, which stands without kiosk nor signage on its hilltop south of Gates Pond, Redemption Rock has both a kiosk and a prestigious roadside marker. Its tiny parcel of land is preserved and cared for by The Trustees (https://thetrustees.org/). More than that, its significance is carved right into the side of the stone itself, which reads:

“Upon this Rock May 2nd 1676 was made the agreement for the ransom of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson of Lancaster between the Indians and John Hoar of Concord. King Phillip was with the Indians but refused his consent.”

As the roadside marker tells us:

“Upon the rock fifty feet west of this spot Mary Rowlandson, Wife of the First Minister of Lancaster, was Redeemed from Captivity under King Philip. The Narrative of her experience is one of the classics of Colonial Literature.”

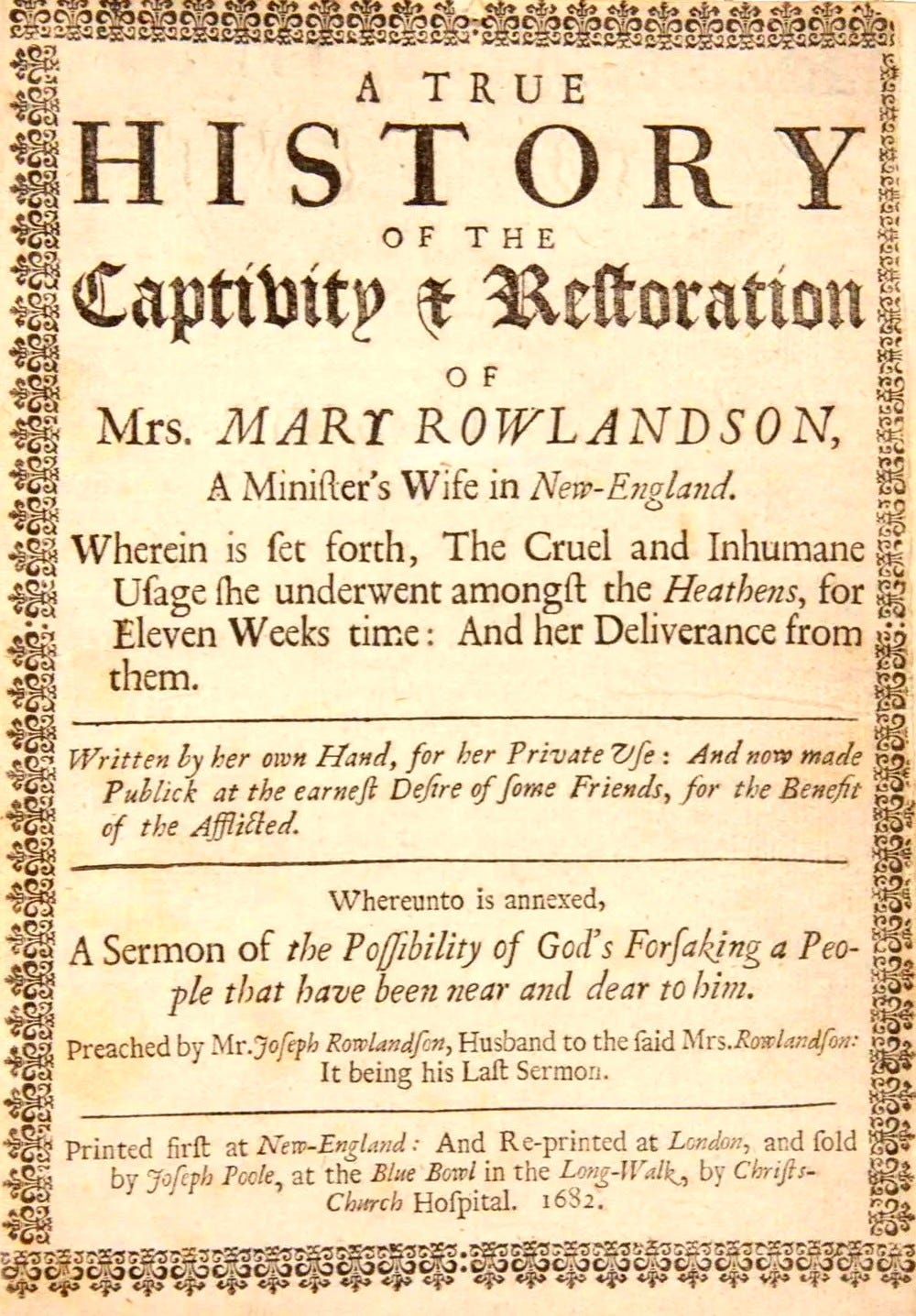

Former captive Mary Rowlandson did later write a book about her time as a hostage, The Sovereignty and Goodness of God: Being a Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, which went on to become the equivalent of a 17th century bestseller, though it’s largely forgotten, now.

Popular histories often skip from the Pilgrims’ landing in 1620 to the Boston Massacre and beginnings of the American Revolution in 1770. But — obviously — a lot went on in the 150 years in between.

Including the bloodiest war ever on North American soil.

I related a little of the background of King Philip’s War in the Rock Of King piece. That boulder was said to be a meeting place for King Philip and his warriors before and after raids on Lancaster and Marlborough. Mary Rowlandson was taken in one such raid.

Here’s a slightly deeper dive into that history.

In the 1670's Princeton was the rugged western frontier for the first British Colonies in Northeastern North America, just beyond the frontier colony town of Lancaster (formerly Nashaway).

The sons of the original settlers of Massachusetts Bay Colony and their families, along with new arrivals, had been pushing further and further inland from Boston and its more immediate surroundings, buying, negotiating for, and claiming, land from its Indigenous Peoples.

In 1675, some of the Indigenous Peoples of the area began resisting and fighting back against the expansion.

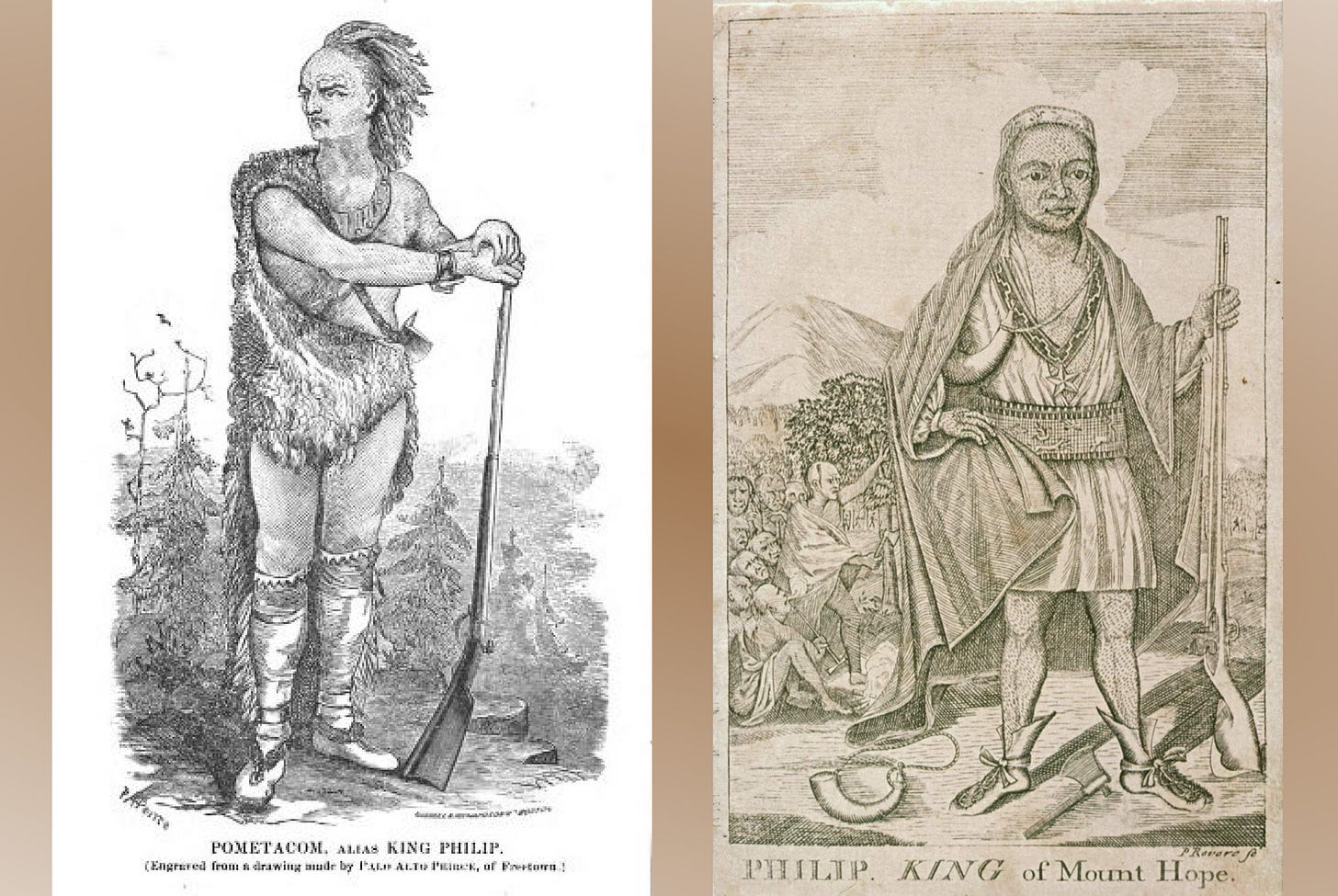

Metacom, a Wampanoag Satchem originally based near Plymouth Colony, was called “Philip” by the Europeans. Metacom was the son of Massassoit, who had welcomed and helped the Pilgrims upon their first landing. But relations soured as the colonies expanded their territories and told the Indigenous Peoples they were no longer sovereign but subject to British Law and the Crown.

In mid-1675, the Colonists pinned a murder charge on Metacom and moved militarily to take him into custody. Metacom not only rejected his guilt in the charges, he rejected their right to be brought against him. He had earlier refused to disarm. He and his people went on the run, and the Colonial forces began trying to hunt them down.

As Metacom and his people evaded their grasp, other Indigenous warriors began striking frontier targets. Towns and outposts were raided. As tactics escalated and casualties increased skirmish by skirmish, the conflict devolved into an all-out war, now known as King Philip’s War — a war which raged so out-of-hand some historians do indeed call it the bloodiest conflict ever fought on this soil.

In a pre-emptive December attack on the Narragansett — who had not yet joined in the war, but had harbored folks loyal to Metacom — Colonial forces didn’t stop with the warriors, going on to kill at least a thousand Indigenous elderly, women and children non-combatants while completely destroying winter homes and wigwams so any survivors were left homeless in the ruins.

Some suggest prominent Colonial women such as Rowlandson were taken captive in order to prevent such tactics, in hopes that Indigenous women would be safer in proximity to captured Colonial women, and Rowlandson did travel for a time with Weetamoo, a prominent Wampanoag leader and kinswoman to Metacom.

Indigenous Warriors inflicted their own death toll in raids and skirmishes. 14 men died in the early February raid on Lancaster, when a combined force of hundreds of Wampanoag, Nipmuc and Narragansett took over the town — and Mary Rowlandson was taken captive.

We know something of her captivity because of her later narrative. After being “removed” several times to spots slightly further west over the next couple of months, Rowlandson was eventually returned to Wachusett, where King Philip was camped, about a mile away from Redemption Rock. Her release was then negotiated and secured, and finalized here at Redemption Rock in early May.

Mary Rowlandson was freed at Redemption Rock, and went on to write her famous book. The war did not end as well for King Philip and the Indigenous Peoples of Southern New England.

On August 12th, 1676, Metacom was shot and killed. His corpse was then desecrated and dismembered, his severed head placed on a prominent pike near the entrance to Plymouth for the next few years.

Captured Indigenous Peoples were sold as slaves and sent off to Barbados, never to see their homes again. Some displaced Indigenous folks sought out new homes and new relations further north and west.

The war didn’t really end with the death of Metacom in 1676, although that was the traditional dating. Battles on the northern front continued until 1678 — and up there, the Indigenous folks won.

And in a larger sense, Indigenous resistance and warfare continued into and through the 18th century, though the Europeans tended to minimize and bracket the conflicts to match up with their own continental battles, as the Indigenous opponents were now often allied with the French.

So, King Philip’s War was followed by King William’s War (1688–1697), Queen Anne’s War (1702–1713), Dummer’s or Greylock’s War (1722–1725), King George’s War (1744–1748), Father Le Loutre’s War (1749–1755), and the somewhat better-known French and Indian War (1754–1763). To name a few.

Wabanaki forces, allied with the French and based in the north, continued to raid Colonial towns and outposts in the south. And take captives. During Queen Anne’s War, three men were kidnapped just south of Gates Pond, for example, as related earlier in my Rediscovering Kequagansett. They were carried up to a place near Montreal, and forced to build a mill at Fort Chambly.

So many wars. So much blood. And yet? We don’t hear about those years or those wars very often. They’re not a publicly celebrated nor publicly condemned part of our culture. They’re just — ignored. We jump from the Pilgrims to the Revolution, skipping over a lot of history.

Investigating stone sites has involved some supplemental education in several disciplines, including history, and it’s been eye-opening discovering how extensive the Indigenous presence was around Central Massachusetts.

I’m not only learning history, it’s coming to life around me. And in learning about Indigenous Peoples’ Ceremonial Stone Landscapes, I’ve discovered some of that history is hiding in plain sight, all around.

There’s an emerging realization that the Indigenous Peoples of what is now Northeastern North America worked with stone, and that some of the structures traditionally assumed to be colonial farm leftovers — some stone rows and cairns, for example — are actually much older.

Some are ancient stone prayers, and parts of Ceremonial Stone Landscapes. Ceremonial Stone Landscapes is the term preferred by USET, United Southern and Eastern Tribes, a nonprofit, intertribal organization of Indigenous Peoples, for these ritual stone work sites in eastern North America.

Amateur researchers and antiquarians have been pointing out the possible Indigenous origins of the stone work since the 1980’s. Over time, more and more professional voices have joined the discussion. Even more importantly, Indigenous voices emerged to confirm the hunches of the researchers had been correct.

Consider how many “Indian Stones” are found around this area. Redemption Rock… King Philip Rock... Many other big boulders bear “Indian Names”, like Sleeping Rock in Berlin. It’s curious how important large stones were to Indigenous Peoples in this area. Several boulders in central Massachusetts are named King Phillip Rock. All are said to be Metacom’s meeting places. There’s one in Berlin, one in Sharon, and one in Winchendon, to name at least three.

Yes. The importance of stone to local Indigenous folks has been this obvious.

As evidenced by Redemption Rock, even in the second generation post-Contact the largest stones were still significant places where Indigenous folks conducted important business treaties and exchanges. Though the English settlers needed to chisel the event into the stone to bear witness, for the local Indigenous folks, the Stone itself bore witness — it was the Witness.

Observing and really taking in Redemption Rock, I tried to understand what made it such a worthy witness for those events of 1676. Its prominence in the captive exchange seemed to suggest the stone itself was likely an older object of veneration for Indigenous Peoples, predating its later colonial use as a meeting place.

There was, perhaps, a suggestion of effigy work to be found in the ledge when regarded from various points-of-view. The ice coating served to give the entire shape a certain uniformity, making it easier to perceive these possible effigy forms. There were several stones added, and perhaps the ledge itself worked in places, to give the suggestion of aquatic animals rising from the depths, from certain angles.

Indigenous effigy work in the Northeast sometimes includes a mutability in its presentation, in that the effigies can change from different viewpoints, each face of the stone presenting a different animal or human “face”.

Talk of animal shapes in the stones may result in some accusing me of indulging in pareidolia, our mind’s tendency to see forms in inanimate objects, like shapes in clouds, or faces on cars. But it’s a mistake to leave imagination out of the equation.

Indigenous People intimately connected with their environment possessed the same capability for imagination that you and I do. The same tendencies toward pareidolia. And in their case, they may have seen adding stones and augmenting the ledge to better resemble an animal suggested in shape to be akin to drawing the spirit of that animal out, and completing a work nature intended by creating the raw form.

Redemption Rock appears to be more than just a prominent landmark at which to meet and exchange a hostage. These subtle embellishments suggest a reverence going back a very long time. There is a significance to this stone, a certain something about it, though exactly what that is may escape us, today.

And Another Thing…

There was also a Stone Chamber and a Stone-Lined Water-work near Redemption Rock. Worth spending some time on in their own right. I’ll give you a look at those in a future installment.

Keep your eyes open for some previously unreleased raw video from this visit, too. I’ve produced a YouTube Video Presentation, but I’ll share some uncut footage with you here on Substack. Now that I can…

Thank you for reading!